- Now You Know

- Posts

- The Thing About Awareness

The Thing About Awareness

Why popularity can be misleading

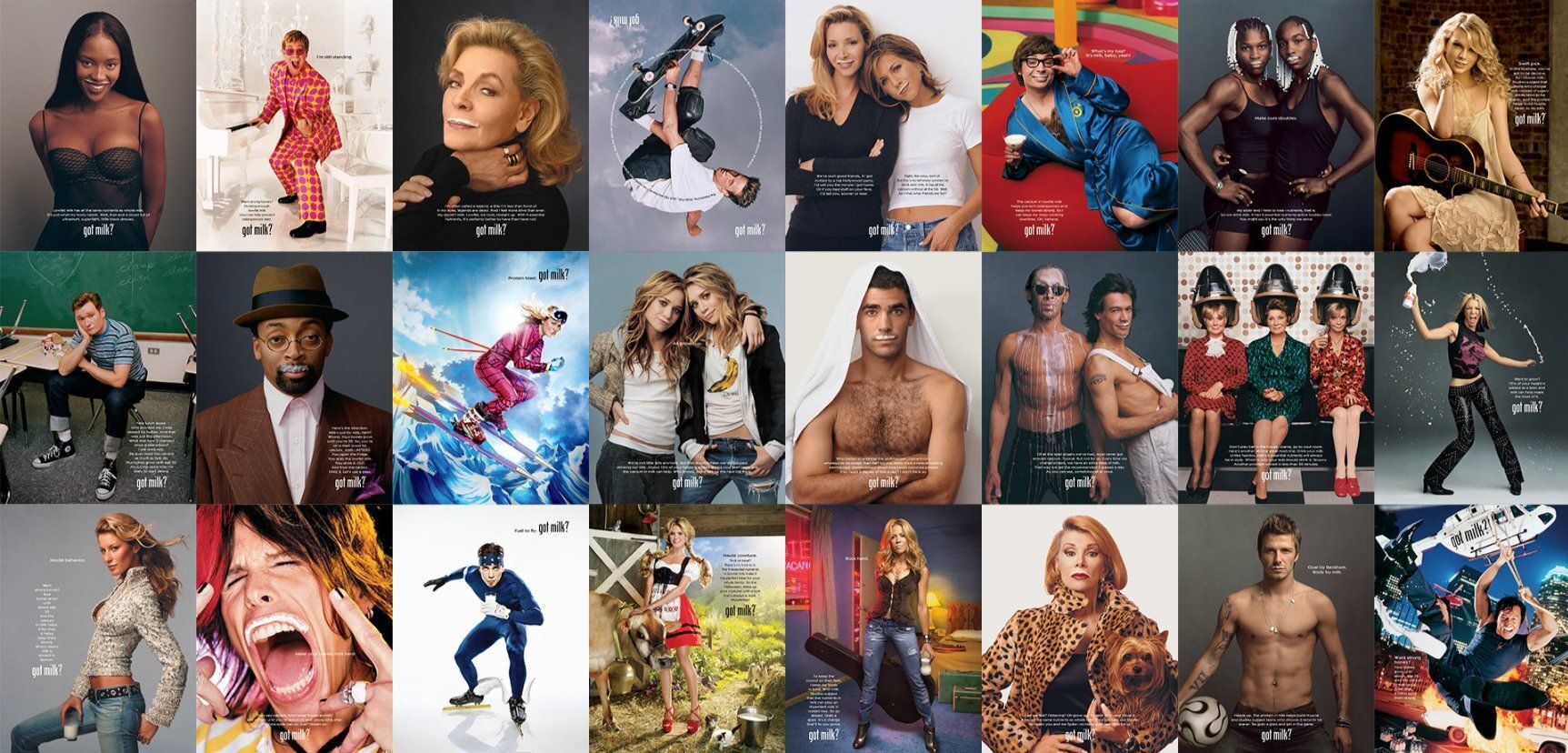

The “Got Milk” campaign celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. You remember the ads that featured photos of celebrities sporting milk mustaches? Yeah, that one. If you were around in the ‘90s, you couldn’t miss it. The campaign was everywhere. According to reports, at one point, “Got Milk” had bolstered up to 90% awareness in the market. Wow. However, despite its popularity, the campaign only managed to increase milk consumption by 2%, against a budget north of $100 million per year.

But how can that be? How can something so seemingly ubiquitous in the cultural zeitgeist be so ineffective at influencing behavior, given its significant investment? It appears as though awareness, though often lauded as an indicator of marketing success, is not as telling as we’d hope. Sure, people have to know you to choose you. However, just because they know you, it doesn’t mean you’ll be chosen. That is to say, it’s not enough to merely be popular in the zeitgeist. The mental availability that comes from awareness doesn’t amount to much if you aren’t meaningful—i.e., full of meaning.

Therein lies the challenge with Got Milk. The meanings we associated with the “milk” brand weren’t nearly as dire or as consequential as the ads suggested. Even though they were able to recruit the “who’s who” of entertainment at the time to don the stache, there wasn’t very much meaning to milk itself.

The Got Milk campaign actually got its start two years prior to the milk mustache aesthetic we have come to know so well. In an attempt to curb declining consumption of milk in the US, the California Milk Processor Board, a non-profit marketing organization founded to promote milk, created a marketing program to get more folks drinking milk. The first ad debuted in October 1993, with a Michael Bay-directed film that featured a young man who missed out on an opportunity to win a radio contest because his mouth was chuck-full of peanut butter, and he had no milk to wash it down so he could answer an on-air trivia question clearly. We’ve all been there, right? No.

Sure, there were definitely moments growing up in the ‘90s when I’d be totally bummed if there was no milk in the house and I was hankering for some cereal. Yes, I’ve certainly experienced that, but the lack of milk in the refrigerator didn’t amount to deprivation as the ads suggested. Milk wasn’t a must; it was a necessity in certain situations—situations that were, themselves, optional. And once celebrities started rocking milk mustaches, it didn’t imbue milk with more meaning. It was a memetic device that allowed more endorsers to participate and served as a mnemonic to remind us of milk. But it didn’t change what we thought about milk—its meaning. Milk was still merely a food pairing, one that satisfied a functional job to be done that was in and of itself substitutable. It was just milk. We may have seen it more, but it didn’t mean much more.

This conflation led to the mistaken identity of awareness for mental availability—but the two are quite different. Awareness is the extent to which something is known or familiar. Mental availability, on the other hand, addresses both the quantity (popularity) and quality (meaning) of the memory structures related to a brand. The Erhenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science at the University of South Australia has contributed a wealth of scholarship that underscores the impact of mental availability on consumption, so I need not revisit the canon here. Any serious marketer should by now know the sway of memory structures on consumption. However, this sway isn’t awarded solely to awareness. A brand can’t be chosen if it’s unknown, but a brand won’t be chosen if what’s known is not well regarded. Its meaning matters, and that’s only half the battle.

I’m aware of plenty of things that I’ll never consume. Cigarettes. Gambling. Alcohol. I know a litany of brands in each category, and I can rattle off their campaign slogans like a jukebox machine. However, I’ll never buy them because I don’t smoke. I don’t gamble. And I don’t drink alcohol. Each of these verticles has a set of meanings that I ascribe to them based on my cultural subscription—who I am and how I see the world. It’s not a value judgement that I place on the categories, per se; it’s just not for me. Therefore, I don’t consume. I know them. I am aware of them, and in some cases, I actually think positively of their associations. I mean, how cool was James Dean smoking Marlboro back in the day? But that’s not enough. Since their meanings are not congruent with my reality, who I am, I don’t buy them. Meaning is only one half of the battle; those meanings must also be relevant to me and my identity project if they are to be adopted.

So, here’s the TL;DR. Got Milk was a clever campaign that drove awareness in the marketplace. However, the campaign brief was to drive consumption, and, unfortunately, awareness alone won’t do that. Our cultural consumption is predicated on something more than awareness. We have to know you, think favorably of you, and find those meanings aligned with our identity to consume. Otherwise, it’s not likely that we’ll buy. You know what I mean?